The second full USA Roller Sports roller derby season has wrapped up, with Washington state pulling off a sweep and Oly taking home two national titles, the men’s (Oly Warriors) and the women’s (Oly Rollers). Thoughts of the event and a complete snapshot of USARS derby, Year Two, will come later in the off-season.

But ahead of that, let’s put on our strategy hats.

All the teams and virtually all the players playing under the USARS banner have very little experience in the faster, more tactical style of roller derby it is trying to develop. Knowing the rules is one thing—at only 10 pages of significance (for now) there is not much to need to know—but applying that knowledge on the track is another thing entirely.

This has been evident during the 2013 USARS tournaments, where teams have been making a lot of strategic mistakes. These mistakes were the major culprit behind some of the more boring sequences of play, including runaway pack situations or instant jam call-offs. These sequences often ended in a 0-0 jam with little action or excitement to show for them.

As with any learning process, these mistakes will pass with practice and game experience. But before one can learn from mistakes, one must know exactly what those mistakes are.

Here are the three most common tactical errors in USARS play over the last two years, from least common to the most.

Mistake #3: Runaway Pivots

In USARS, pivots are granted their traditional ability to break away from the front of the pack and become a jammer, but only after the opposing team has already gotten their jammer out for lead. This ability is most useful when a pivot is controlling the front of the pack, which lets them immediately spring into action should their jammer fail to clear the pack first.

A big chunk of USARS tactics is how the pivots do battle with each other, both at the start of the jam and during the rest of the initial pass sequence. In most circumstances, a pivot will want to be in front of the opposing pivot at all times, to help suck them back into the pack or delay them should they need to break away after the jammer.

Most circumstances. But not all circumstances.

Pivots hell-bent on getting to or staying at the front of the pack during the initial pass hurt a team’s chances of scoring points more than it helps it. This is a mistake made by pivot players new to USARS, and the traditional pivot position in general.

The logic behind this is simple: The scoring player with the best chance to score points on a jam is (generally) the first one reaching the back of the pack on a scoring pass. The first jammer to reach the back of the pack is (usually) the one that gets out of the pack first on the initial pass. The first jammer to get out of the pack is the one that (always) get the most blocking help and assistance from his or her teammates in the pack.

Therefore, that works together to make sure their jammer gets out first is well on their way to scoring points. However, a pivot trying too hard to stay ahead of everyone else will wreck this calculus by effectively taking themselves out of play, reducing the blocking power that their jammer might need to do that. A pivot race at the front of the pack can also ramp up the speed of the pack to hopelessly high levels, making it much harder for blockers to stay together or be effective.

Here is a video that shows an example of this happening during a jam. Focus on the white blockers and the white jammer and see how quickly they fall behind due to the white pivot racing the pack forward:

The white pivot ultimately got the position she wanted, the front of the pack. This put her in good position to chase the black jammer out without resistance on the part of the black team.

However, in doing this she left the white jammer in the dust and left the other white blockers vulnerable at the rear of a fast pack. She also put herself out of play ahead of the pack, forcing her to drop back into pack before she could legally activate her jamming abilities. This gave the black jammer a pretty easy scoring pass, picking up two free points.

But more importantly, in playing the jam this way the white pivot was basically guaranteeing her team would not score any points before the initial pass was even completed.

It is important for pivots to stay at the front of the pack in case they are needed to salvage a team’s offensive chances on a jam. However, pivots cannot ignore their defensive responsibilities. Pivots must maintain pack speed control for their team and make sure the opposing jammer does not break through the last line of defense—themselves.

After the initial burst off the line, the white pivot did not take stock of her team’s current situation, which was quickly turning sour: The white team missed their initial blocks, allowing the black team to get by all of them. This let the black team swarm the white pivot, creating the fast pack that doomed the white team from the start.

In this situation, a pivot would be more effective for her team by locking on to the opposing jammer (or any blocker in her immediate path) to slow her down. Doing this would check the speed of the pack and attract the attention of opposing blockers just enough for her teammates to catch up and regain containment, getting them and their jammer back in the play.

You can pause and manually advance the slideshow if it is moving too fast to read!

Note that in playing defense like this, it is likely that the pivot will get sucked back into the pack, reducing their effectiveness as an offensive option. But as long as the pivot sucks the opposing jammer into the pack with them, that’s just fine. A pivot recycling the jammer to the back and giving the rest of her team a chance to keep containment on the other blockers is exactly what they should be doing as the leader of the pack.

Defensive containment is ultimately the number one priority of a pivot. Players new to the pivot position will need to recognize when to override their offensive desires with the defensive needs of the rest of the team. Although good pivots will occasionally steal away points in tight jammer races, the best pivots must know when to flip the switch from offense to defense by doing whatever necessary to hold back the other team long enough to make sure their jammer is the one leading the way.

Mistake #2: Striking Out on the Grand Slam

As in all forms of roller derby, getting lead jammer status is important. But in a true team game, lead jammer is only half the battle. In USARS, if blockers are not constantly working to contain the opposing blockers within a pack, all those potential points could escape, speed the pack up, and put a scoring opportunity out of reach. If that happens, the lead jammer position is worthless.

In a perfect world, a team will be able to get their jammer out for lead while simultaneously holding back the opposing jammer at the back of the pack, absorbing the opposing pivot from the front of the pack, and containing the opposing blockers from breaking one of its scoring players out on a scoring pass in response. When two teams of unequal strength play each other, the better team will tend to do this a lot, obviously.

But in closer match-ups, getting a jammer out unopposed for a significant amount of time is very difficult given that a team without a jammer in the pack will automatically find themselves at a temporary manpower disadvantage, one the other team will use to get their jammer or pivot out of the pack—usually very quickly.

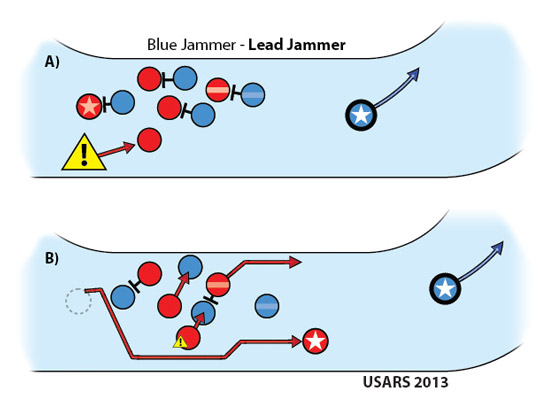

(A) 5-on-5, the blue team gets their jammer out first and is in decent position to hold back both the potential scoring players on the red team. However… (B) The blue team must maintain blocks during a 4-on-5 disadvantage, something one of the uncovered red players can exploit to help do some offensive blocking and free their jammer or pivot in response.

Trying to play defense against that many opponents almost demands that the pack keep moving as to give blockers more time to work with. A fast pack makes it harder for players to advance their relative position without the aid of a teammate, either with a block to slow opponents ahead or a whip to fling a player past them more quickly.

However, if a fast pack is good for defense, it is simultaneously detrimental for a team’s offensive chances. A fast pack makes it all but impossible for a lead jammer to catch back up to it to score.

Which brings us to USARS strategy mistake number 2: A team with lead jammer tries to contain everyone on the other team for too long, creating a fast pack they risk losing control over, potentially leading to a runaway pack situation and no score.

The longer a team needs to play defense during a jam, the more likely it is that it will make mistakes as fatigue settles in. As the defense breaks down, the pack will start speeding up to compensate. As the pack speeds up, it will also speed away from the lead jammer. If it gets too fast, the lead jammer will be forced to call it off with no hope of catching up to score, even if she had a big distance advantage over the opposing jammer.

A team with lead jammer can be tempted to commit all their defensive resources on the opposing position players, so as to prevent them from getting out of the pack at all. But given the natural 4-on-5 disadvantage it needs to overcome to do this, it is inevitable that the defense will overdo it and let the opposing blockers start gaining forward pack position. Once that happens, the domino effect will take over and the other team will keep pushing to the front, speeding up the pack to the point where it is going just as fast as the jammer trying to catch back up to it.

Which is why in most situations, the best and most realistic chance a team with lead jammer has at scoring safe points in a jam is to let the opposing jammer go well before things get out of hand.This will make sure the blockers containing opponents in the pack are moving fast enough to play effective defense in 2-walls or one-on-one, yet slowly enough for their jammer to be able to come back around on offense and score.

Because if the 4 tries to do too much against the 5…

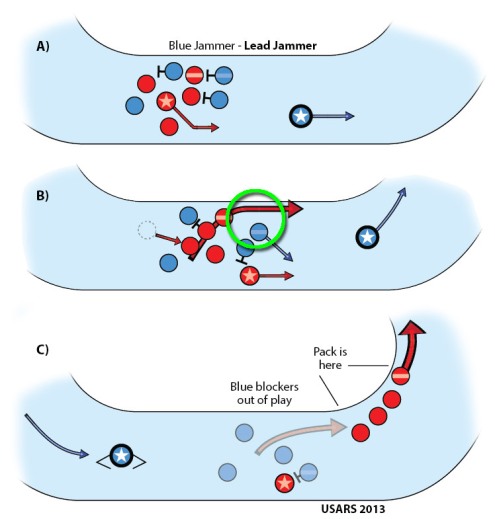

(A) The blue jammer gains lead while the red jammer makes a break for it on the outside. (B) Eager to hold back the red jammer, the blue blockers covering the front of the pack move out to stop her. (C) However, this opens up an inside lane for the red blockers, who jump to the front and speed the pack away, preventing the blue jammer from scoring. In this situation, the blue pivot needs to keep the opposing blockers on the inside covered (green circle)—even if that means letting the red jammer escape—to make sure at least one goat is secured so they can bank some points on the jam.

This is a difficult concept for teams new to USARS. A lot of them have been trained to think that “safe” points are the ones where the jammer, and only the jammer, is kept behind a nice, solid wall of blockers, giving them plenty of time to comfortably pick up a grand slam, or at least a full four-point pass.

However, in USARS, it is (by design) extremely likely that both teams will have a scoring player out on the same scoring pass on every jam, often with little distance between them. For this reason, a team cannot put all their defensive eggs in the initial pass basket and expect to count their points before they hatch. An opposition team has three ways to reply to the lead jammer—a jammer breakout, a pivot breakout, or the blockers gaining pack control and pulling away—so expecting to hit a home run ball by using the same old defensive strategy every time will only result more strikeouts.

Instead, teams need to play small ball, working to get the sure singles and doubles. Even if it means sacrificing a potential-but-risky grand slam opportunity, the team with lead jammer must know when to stop focusing on absolute jammer defense and start concentrating on trapping opposing blockers, so that they can best use their blocking resources to slow down the pack and bring home one or two “safe” points as the jammer comes home to score.

Mistake #1: Fraidy-Cat Call-Offs

Mistake #2 leads directly into the #1 mistake that players new to USARS roller derby make. And it’s a really, really big one.

The lead jammer (or as USARS officially calls it, “lead active scorer”) has the power to call off the jam at any time. But this power can transfer to the opposing jammer (or pivot!) should they pass the leading jammer. Be they jammer or pivot, the lead scorer must always be the scorer in the lead, as USARS would say.

The bad news for USARS hopefuls: It seems as if a terrible habit has developed among the greater roller derby jammer population.

For some strange reason, jammers embattled in close jammer races default to calling off the jam before getting anywhere close to scoring position. It appears that they prefer taking a “safe” 0-0 jam outcome instead of doing their job—trying to score points—and having faith that their teammates will do their job and make some blocks to help them score—whether their team has lead status or not.

To put it bluntly: Jammers are ending jams far too early with pussy fraidy-cat call-offs, far, far too often.

You will see this a lot in USARS, especially in the early going of its roller derby program: The jammer breaks out of the pack, the pivot (or jammer) gives chase immediately, then the lead jammer calls off the jam for fear of getting passed, losing control of of the jam to the other team, and potentially letting them score points before they call it off themselves.

However, this “fear” of a jammer losing control is a misplaced one. Even with the ability to call it off—and the potential consequences of losing that ability—the lead jammer does not control the jam.

Yes, you read that correctly. The lead jammer position is overrated.

To prove the point, ask yourself: Why does a jammer call off a jam?

Have the opponents in pack clogged things up ahead of the lead jammer, preventing her from continuing forward safely? Is the lead jammer seeing that her teammates in the pack can’t effectively block the opposing jammer on her scoring pass? Did the team with lead jammer not keep containment on the opposing blockers, leading to a runaway pack situation?

In truth, the pack has more control over the termination of a jam than do the jammers. (With 80% of the players on the track, it bloody well should.) All the jammers are doing when choosing to call it off is reacting to what the pack is doing–or is often the case, not doing.

This is the biggest, most terrible mistake USARS jammers can make. On the verge of losing lead status in no-man’s land, a jammer desperate to put hands to hips without even considering what is happening in the pack is often throwing away a perfectly good scoring chance.

Favorable player personnel match-ups, relative pack position, penalty advantages, and the overall game situation should override any (false) fears of a jammer temporarily losing the ability to call off the jam. Because the jammer is not the one calling off the jam. In the end, it is the blockers in the pack that dictate when the jammer cries uncle.

Practically, if your blockers are doing a better job than the blockers on the other team, all calling it off early will achieve is to discard their hard work and waste the advantage they earned in the pack. Because at that point, who cares if the other jammer passes you? Let them decide if entering the pack first in an unfavorable scoring situation it worth it.

Deliberately allowing the opposing jammer/pivot to reach the rear of the pack first is a heavy concept, but stick with me. Here is an example to demonstrate why this is usually a good idea.

The blue team has managed to put together a 4-wall on a single opposing blocker, slowing the pack to a (rules-mandated counter-clockwise skating) crawl. This is their ticket to getting lead jammer, but it’s also a recipe for an immediate chase by the red pivot, seeing as she was left uncovered at the front.

The race is on. As it turns out, the red pivot is faster than the blue jammer, and will pass the lead jammer about halfway around the track.

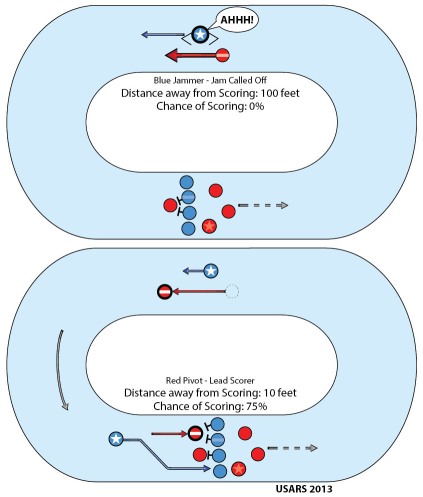

A fraidy-cat jammer (AHHH!) would immediately end the jam to make sure the red team won’t score any points, at the cost of giving her team a 0% chance doing the same.

A real jammer—a team player—would be confident that her teammates could keep that 4-wall strong long enough for the opposing team’s scoring player to crash into it without scoring a point. This will allow the jammer time to regain any distance lost after getting passed for lead status along the way, which for a competently fast jammer should only take a moment, and generate a much more realistic scoring chance for her team than she would have got with a cowardly call-off.

Jammers afraid of losing lead status are afraid to score. With solid team blocking to support them, teams can generate points even during situations where they might lose lead jammer status along the way. If you were the blue team and needed points, which one of these situations would be better for you?

Look at the second example above. Because the blue blockers are in perfect defensive position, the conundrum of when to call off the jam suddenly falls on the red team. Does she try to shove her way forward for a point? Does she risk squeezing to the outside, potentially losing the ability to call it off if she gets knocked out of bounds?

Should she just do the “safe” thing and end it 0-0 before the blue jammer sweeps around the red goat in the blue goat pen?

The idea behind the “always try to score” strategy is that teams will find more points if their jammers just put their heads down and get to the rear of the pack as quickly as possible, whether they lose lead status along the way or not. Assuming a jammer has decent blocking to back her up, it is infinitely more advantageous for her to be a fourth-whistle length away from scoring and have the other team end the jam 0-0; than to be half the track away from scoring and ending the jam 0-0 herself.

The closer you are to the business end of pack, the more likely you are to score due to mistake from the opposing team or a good play by your own teammates. The more you get into this position, the more points you will score in the long run. Ultimately, these fringe points can be the difference between winning or losing, especially in competitive USARS games where double-digit jam scores are unlikely and reaching 80 total points is merely extremely difficult.

Of course, there is risk in approaching the game like this. If your team is the one that makes a mistake or is the victim of a good blocking on the part of the other team, a play could backfire and you may lose more points on the jam than you could have potentially gained.

However, the great teams will understand this risk and learn to manage it and how to spread it out across different game situations within a single bout or an entire season. While individual jams (or even a whole game) may go badly, a better team will know that if it plays the percentages (and stays out of the penalty box) it will score more points than it gives up throughout a 60 minute game, win more games than it loses across a season, and ultimately have the knowledge and trust in one another to win a big game when it matters the most.

Consider if the above example happened multiple times throughout a game. Across four jams, let’s say. In a still-close jammer race, the red pivot (lead active scorer) will not have much time to work against the wall. Working off that, let’s assume he could manage to break through it (with one blocker to assist, the red goat) and call it off successfully 25% of the time. And just for the heck of it, let’s guess he picked up a loose point in one of the jams, too.

This means that in 4 jams where the red team had a scoring player enter the pack first, it picked up 5 points.

But think of what might happen in the other three jams, given the superior defensive position of the blue team in the pack.

In one, maybe the red pivot calls it off a hair too late and allows the blue jammer to steal the goat point before the fourth whistle. In another, maybe he does call it off too late after scoring on the loose brick in the blue wall, allowing the blue jammer to retake lead status, score on 3 red blockers, and call it off before the red pivot can do any real damage. And in yet another jam, maybe the blue wall escorts the red pivot out of bounds (preventing him from calling off the jam), giving the blue jammer plenty of time to pass back by the red scorer, take all 4 points in the pack and then call it off—or maybe, trust his blockers to make a go at another scoring pass.

So while the red team may have gotten through the wall once in four jams and picked up 5 points, over the course of several jams it is totally feasible that, with total pack control and solid defense during the scoring pass, the blue team will have picked up 8 points or more.

Had the blue jammer chickened out and called off those four jams without ever attempting a scoring run, the blue team would have scored zero points.

Which score differential would you rather have: 8-5, or 0-0?

This is the mistake that teams new to USARS are making when they call off the jam too early. It is a twofold mistake, actually: Jammers afraid to begin a scoring pass as second banana are too worried about what points they might lose in the immediate future, rather than thinking about the points their team may gain in the long run. And jammers that do not practice taking a tardy plunge will not give their team enough data or experience to make better risk management decisions in all game situations, not just the safe and easy ones.

If USARS teams stipulate—for training and scrimmaging purposes only—that jammers (or pivots) are forbidden to call off the jam until someone has scored a point, they will be shocked at how often they can score in seemingly unlikely scoring situations. It will also teach teams how to best position themselves on defense for the scoring pass, and how their actions during the initial pass can help or hurt them in that regard. (See: Mistake #2 and Mistake #3.)

Best of all, it will train jammers to trust their blockers on a scoring pass, teach blockers how to block better as individuals and a group, and make a team believe can score in any situation if it has the faith and ability to pull it off.

Unless, of course, the team is afraid of making mistakes.

Posted by toddbrad on 5 November 2013 at 7:57 pm

These seem like straightforward mistakes that a team with good coaching could easily eliminate with more experience. However, it sorta seems like the only region where teams are getting serious experience is in Washington State. The entire rest of the country has such a low population density of USARS roller derby teams that it’s a major undertaking for them to travel to the nearest city with a team to challenge (for example, there isn’t a single USARS team in a 500 mile radius of me). It seems like this is gonna make a positive feedback loop – the strong teams get stronger and the weak teams get weaker. What do you think USARS must do to build a network of teams to enable those outside the Pacific Northwest to get enough experience to fix these problems?

Posted by WindyMan on 5 November 2013 at 10:50 pm

Get people to read my blog! *rimshot*

But, seriously. All USARS needs to is make sure it has a consistent base of teams playing its rules that have patience to help build things up and spread things out. As long as it makes improvements on their end (the rules and the organization) and keeps getting the word out as a WFTDA alternative, like with more appearances at RollerCon and other derby events, the more likely new USARS leagues will form or existing WFTDA-playing leagues will co-adopt or switch.

All it takes is one in an area to seed many more, and once that happens teams can start more realistically playing each other. But if it’s going to happen, it’s going to take time. I think the USARS Roller Derby arm understands this, so it won’t push too hard until it thinks it’s good and ready to.

Posted by joseph l. simonis on 6 November 2013 at 11:30 pm

You hit the nail on the head in terms of regional opportunities in USARS 2013. Seriously, the closest team to us (I skate with Chicago) that legit played USARS this year was Tulsa, and that’s about 700 miles away. But that distance is about to shrink immensely, as our first game in 2014 is against the Happy Camper Roller Girls, a new USARS league in Ft. Wayne, IN. As USARS grows and spreads more geographically, you’ll see a lot more teams get a lot more (high-level) competition each year leading up to tournaments.

Posted by Lyxar on 6 November 2013 at 4:58 pm

Okay, so you brought up a scenario i previously didn’t give enough attention to. However, that scenario (most distilled in that diagram, where you do scoring chance estimates, and basically ask “would you rather have 0% chance to score, or 75%?” is incomplete as well.

See, you say such early call-offs would become much less frequent, if players become more experienced, skilled and smart. But in said diagram, you only consider a smart initial lead jammer, not a smart opposing scorer. Why? Well step by step:

1. Initial lead does not call it off, even though he/she is about to lose lead. Reason: His/her blockers are better positioned (that 4-wall).

2. Opposing scorer overtakes, and becomes lead scorer (meaning: now he can call it off!)

3. Opposing scorer approaches the pack, and see’s the giant 4-wall. What is he/she going to do next? Well he prefer a “25% score chance” over a 0:0 jam? Because, as soon as the other jammer will approach the wall, he will probably overtake again in turn, and thus become the lead. He/she will then probably score, and our opposing scorer loses the ability to prevent that (calling it off).

TL/DR: If both scorers are smart, that scenario will lead to an early call off, either way. The only thing that has changed, is that now it is in the opposing scorer’s interest to call it off, instead of the initial lead.

That scenario will only NOT lead to an early call off, if the initial lead does not lose lead status.

Posted by Lyxar on 6 November 2013 at 5:18 pm

P.S: My “bigger picture”-argument, which so far i have only been hinting at, is that the game is statistically biased towards call offs. There are more cases (initial lap scenarios) and improbabilities (lapping the opposing jammer, to get beyond the 4-point advantage score-brickwall) to call it off, than there are cases and probabilities to continue the jam.

And if that’s the case, that’s not an issue of skill (though, lack of skill/experience can certainly amplify existing biases).

Posted by WindyMan on 6 November 2013 at 7:57 pm

I’m not considering the opposing scorer, because the opposing scorer isn’t the one making the mistake.

It’s okay for a jammer to end the jam 0-0 when things aren’t optimal, and that will inevitably happen often in a game played between evenly-matched teams regardless of the ruleset being played. (What usually happens when both jammers get out of the pack at the same time in a WFTDA game?) But it is not okay for a jammer to call off the jam from so far away from the pack when her teammates are in a dominant or otherwise advantageous position.

Your argument is that the opposing jammer pass for the lead and just call it off in response to a solid wall and no real scoring opportunity. Sure, but that’s not the point. In my example, I’m merely stating that the choice for the initial lead jammer in this or other similar situations is to either call off the jam early with a zero percent chance of scoring points with lead jammer, or let the jam play out and have a non-zero percent chance of scoring points without lead jammer. In that, if an opposing blocker makes a mistake in the pack, you’re not going to capitalize on it from 100 feet away.

In any event, as jammers learn how to skate faster and to better positionally block out in the open (two things that have everything to do with skill), that non-zero chance will become larger as a lead jammer can start making more opportunities happen with less and less of a lead over the chasing jammer. The idea here is that once a team starts believing it has the speed, blocking skills, and team strategy to score in almost any jammer race scenario, it will start to get more of the “risky” points that the other team may be afraid to go for.

Of course, when both teams believe they have the speed, blocking skills, and team strategy to score in any situation, that’s when roller derby is at its absolute most exciting. There was a lot of that in the Oly/Your Mom men’s final at USARS champs, albeit around the boring jams where no one had the chance to engage each other because of rules that were obviously broken (and are already fixed for 2014).

Posted by 3j0hn on 6 November 2013 at 9:00 pm

Watching the USARS tournament, I was actually thinking that a rules change to prohibit call offs until the lead jammer (active scorer) has re-entered the pack (if not scored points) would save spectators from a lot of boring 0-0 call-offs. I guess your argument is that you don’t need a rule, because it good strategy in most situations to operate as if this were the rule. So maybe such a rule belongs in WFTDA where the 0-0 call off is good strategy (but still boring to watch).

Posted by WindyMan on 6 November 2013 at 10:53 pm

Tight jammer races (which I define as two jammers entering the pack within a quarter-track distance of each other) in the WFTDA are extremely rare because they are high-risk with little to no value available. Trying to go for 1s or 2s in a tight squeeze isn’t worth potentially giving up a power jam as the jammer tries to force her way through a tight rear 4-wall with no realistic hope of offensive blocking support.

The way I figure, jammers would need to be confident that they would score minor points in at least 10 tight jammer race situations to mitigate the risk of one jammer penalty. Given the high frequency of penalties and how points in the WFTDA are easy to score in big bunches (“big” meaning four or more at a time), that is a very, very stupid risk to take.

So of course calling it off 0-0 is a good strategy in the WFTDA! But that just goes to show how wrecked the WFTDA game is at the moment: It is better for jammers to not try to score points in many situations. That is so anti-roller derby it’s not even funny.

Anyway, as I’ve argued many times, and demonstrated many more, you don’t need to make a rule to force a team to do something if you make it in their best interests to do it. If you reach a juncture where you need a rule to artificially force a team to try to score, something is seriously, seriously fucked up. Because shouldn’t they try to score 100% of the time?

Posted by Southbay on 7 November 2013 at 12:11 pm

I don’t know if this is true or not, but it’s interesting.

USARS Announces Rules Beta Testing

http://www.derbynewsnetwork.com/2013/11/usars_announces_rules_beta_testing

The last paragraph is of note:

“0-0 jams will be eliminated by requiring the lead jammer to pass at least one opposing blocker before calling off the jam.”

Posted by WindyMan on 7 November 2013 at 12:29 pm

Yeah, I saw that. Honestly, that doesn’t make sense given that the “beta” changes reported on in the article bear little resemblance to the beta proposals USARS drafted last month and offered to leagues to test. (You can see those in PDF form here.) Not that I distrust DNN as a news source, but since I’m usually the first one to get tipped off on USARS-related developments I’m surprised this seemingly conflicting beta came out of nowhere all of a sudden. I’ll double check.

But if it is true, it’s disappointing but not surprising. There are certain things I feel that you don’t need to make a rule for, because if the rules are done right those things will happen naturally. For example, putting a rule in for required forward motion. I hate that it’s in there, but I understand why it needs to be in there. This would fall under the same category, if they’re actually doing it.

Posted by WindyMan on 7 November 2013 at 11:37 pm

Yup, I can confirm that USARS is testing this new stuff, for sure. If the “can’t call it off until you score” clause is officially adopted, the “always try to score” strategy will become mandatory. I guess that’s a good thing given that USARS teams are still apprehensive about being aggressive during a scoring pass. But I’m a stickler for wanting to see the most “pure” form of roller derby possible, with no artificial (rules) additives. Maybe someday that rule won’t be needed anymore…

Posted by Lyxar on 8 November 2013 at 7:15 am

Can someone explain to me, what the purpose of “calling it off” is? My intuitive impression (without knowing history), was that it originally was there to prevent boring jams – situations where the scorers cannot score – thus ending the jam before the clock runs out. But it seems a lot of people think it has a tactical/gamemechanic purpose. If so, what purpose would that be?

Posted by WindyMan on 15 November 2013 at 10:03 pm

Calling off the jam allows the lead jammer to end the current jam at a time of his or her choosing. But there are a few underlying tactical considerations behind that.

The most obvious and common decision a lead jammer has to make in calling off the jam is to do it in such a way as to maximize the number of points he or she scores while limiting the number of points the opposing jammer scores. Call it off too early, you may leave points on the table. Call it off too late, you could lose points as the other jammer comes into the pack.

There are also considerations to call jams off sooner or later to save/burn game clock, clear teammate penalties, or to carry penalty advantages into the next jam. Also, if a jammer feels a scoring opportunity has evaporated, they can opt to call it off figuring that all continuing will do is needlessly tire them and their team out. (Calling it off is one of the counters to the runaway pack situation.)

Historically, calling off the jam was only one of many ways a jam could end before the jam time limit. If the lead jammer fell, went out of bounds, committed a penalty, or got sucked back into the pack, the jam was instantly over, even if one of these actions resulted in an opposing jammer passing the lead jammer and gaining lead jammer position. The modern translation of this concept disallows a lead jammer from calling off the jam if they are out of bounds and/or off their skates, making it possible for the opposing jammer to swipe lead status on the fly.

These cutthroat jam-ending rules can apply to both jammers (except in the WFTDA, naturally) since lead status can switch mid-jam depending on which one is out in front. However, the misunderstood and oft-ignored other side to this equation is that this results in both teams having a powerful set new defensive strategies at their disposal, including the fact that a moving pack makes defense easier to play in general. Basically, if a team is too worried about losing lead jammer status for [reasons], they’re forgetting that those same [reasons] is how they can potentially get it back in the same jam.

So in the context of your questions about the lead jammer calling a jam off (too) early and settling with a 0-0 score, the reason why it’s usually the worst thing to do in a rules environment like USARS is because of these additional defensive strategies, tied to how jammers can or cannot call off the jam and how that applies to both teams equally. Teams that practice these strategies often and are brave enough to use them in actual gameplay will open up more scoring opportunities that they wouldn’t have had otherwise.

But just opportunities—what teams do with them comes back to how good a team is with individual skills and teamwork. But the more chances you have to use what you’ve got, the better.

Posted by Lyxar on 16 November 2013 at 8:53 am

Thanks for your explanation. I understood most of those things, except of the historical context. I should have phrased my question more clearly.

What i meant to ask, wasn’t how “calling it off” can be used by jammers. Since the one who can call it off, can determine when the jam ends, that of course obviously has lots of tactical uses. But that’s not what i wondered about. After all, one could invent any random and significant rule, and then come up with ways how they can be used.

What i wondered about, is what purpose this serves for the game overally. Like, with a lot of the rules, there is a theory behind them why they are there. Like “If there weren’t rule X, then Y would happen” or “This feature X balances out that there also is feature Y”, and so on.

So, to phrase it different this time: What “role” does the ability to call it off play in the game, and what was it originally meant for?

I’m asking because – assuming we want roller derby to first be a race, and secondarily a game about tactics (this does not mean, that tactics are unimportant – we’d want both, but when we’re forced to decide between both, we give “the race” the benefit) – assuming this, if “calling it off” does not play an important and wanted role in the game, then all it does would be preventing races, right? (exception: the “both scorers cannot score”-situation, which of course is undesired anyways, because all it does is wasting everyone’s time and energy for no reason).

The thing is: When people talk about things, they often take the current situation for granted, and then base all their considerations on what is already the case. This promotes incremental “evolutionary” proposals, which often ignore that maybe the premises are wrong to begin with.

Posted by WindyMan on 16 November 2013 at 10:11 am

Ahhhh, I understand what you’re asking now. It’s a really good question, actually.

The whole idea of calling off the jam early is to ensure that the team that’s best at passing opponents is the one that ends up with the most points at the end of the game—and that the one with the most points at the end of the game is the one that’s best at passing opponents.

This is not as obvious a concept as it looks. I’ll explain.

Imagine if Team A was able to complete a pass in 25 seconds, and Team B could do it in 30 seconds. If a jam was two minutes and could not be called off before its conclusion, here is what that jam would look like:

Team A: Start (2:00) Initial (1:35) Scoring (1:10) Scoring (0:45) Scoring (0:20) Partial? (0:00) End

Team B: Start (2:00) Initial (1:30) Scoring (1:00) Scoring (0:30) Scoring (0:00) End

This jam could end 16-12 in favor of Team A, depending on what they do in that last 20 seconds. But could very well end 12-12, too. It’s pretty clear here that Team A is better than team B, since they are scoring faster, but that may not be reflected in the points differential, especially it winds up tied.

Now take this same jam, but add the ability for the lead jammer to call it off:

Team A: Start (2:00) Initial (1:35) Scoring (1:10) End – called off

Team B: Start (2:00) Initial (1:30) Partial? (1:10) End

This jam could end 4-0 for Team A, depending on what they do in that 5 second advantage they’ve built up. But it could also end 0-0…which would be okay, since neither team would have demonstrated which was better on that particular jam, justifying no score on the play.

The “role” that ending the jam early fulfills is to cut out the fat from jam score differentials, to make sure all points gained are a true representation of opponents lapped in the race to the back of the pack. Calling off a jam allows a team to “bank” whatever small advantage their jammer won up to the point where the jam (nee race) ended, an advantage that takes the form of opponents passed for points.

If you don’t allow jammers to call off the jam, you get inaccurate and inflated point totals that don’t accurately represent that, in the context of what roller derby actually is. That is to say, a 4-0 jam and a 16-12 jam tell us exactly the same thing about two teams: One was slightly better than the other.

However, when you have a game where scoring a lot of points is relatively easy, those point differentials can get out of hand pretty quickly and affect the “true” outcome of a game. Flat Track Stats did an analysis of how often leads are “erased” in games, but when I asked if the same analysis on lead increases would yield similar results, FTS was surprised that it mirrored pretty much exactly. That is to say, teams are equally putting up and giving up big score differentials, but people don’t notice this since they’re only focusing on the comebacks.

This is why points swings in the WFTDA are becoming more spurty, rapid, inconsistent, and unpredictable: More and more jams are going the full two minutes because of double not-lead-jammer situations. Games between two otherwise equally matched teams often end in 50-100+ blowout scores is because some of those inflated points differentials (power jams/2min jams) fall the wrong way at the wrong time, producing a false indication of which team was better and by how much.

The only way to balance this is to ensure both teams have a jammer (and pivot, as in USARS/MADE) on the track at all times. But more crucially, whatever jammer is the lead jammer must also have a pressing reason—and guaranteed ability—to end the jam early. Otherwise, many of the points scored will have no meaning or value.

Posted by Lyxar on 16 November 2013 at 7:03 pm

Thank you! This was exactly what i was looking for, and yes i wasn’t aware of this issue. It finally gives me a better big picture of the current situation, instead of just noticing “symptoms”.

It also is very interesting, because it seems that this “reason for calloffs to be there”, is not actually fully solved by the calloff mechanic. That is: Calloffs address the issue you explained, but they do not entirely solve the problem, and that in turn is the reason for the current problems. Let me explain:

The problem is that opponents are not evenly distributed across the track. If hypothetically, opponents were evenly distributed across the track, the issue you explained wouldn’t exist, because the situation on the track would perfectly represent how good each scorer is at passing. And not just passing, this impossible theoretical scenario, also perfectly represents how good each team is at defense (this answers the unasked question: “But shouldn’t a team also be judged, by how well it can defend/block?”).

Now, of course this theoretical situation isn’t the case. In fact, pretty much the OPPOSITE is the case, because of “the pack”: Everyone but the scorers are tightly concentrated on a single spot of the track, which creates some kind of “threshold for scoring” on the track. Each scorer only gains points, when passing through this spot on the track – the rest of the time he spends racing the track, he doesn’t get points awarded at all (exception: lapping the opposing scorer, who also is a single “spot on the track”, that is passed only in long intervalls, thus creating a second “score-threshold”).

The existence of those scoring-thresholds is why one cannot simply pick a random point in time, and know how good a scorer is compared to the other (and also not how good each team is at defense, compared to the other). Hence, we make the lead scorer the “judge” about at which point in time to make a judgement (if you could follow this train of thought until here, this also makes WFTA-style “lead status doesn’t change” make no *censored* sense – it completely ignores the original purpose of the calloff-mechanic!).

So, let the lead scorer call it off, and everything is fine? Sadly, no. See, it is not just the end of those 2 minutes, where this score-distortion can potentially happen. It happens every time “the pack” is passed by a scorer (and additionally every time the opposing scorer is lapped, which creates another serious problem). As a result, the lead jammer does not just get to decide the “how long the jam should be”. This is hard to explain with words, even though it should be obvious, so let me show it with examples:

If the calloff-mechanic would only address the original issue (your example), then the scorers would always let the jam continue until the clock has almost run out. The lead would only call it off when:

1. There is not enough time left on the clock, for the lead scorer to score significantly more.

2. BUT there is enough time left on the clock, for the opposing scorer to score significantly more.

So, “the race” would always run as long as it is possible without “distorting” the final score. Almost every jam would last over 1:30mins.

Obviously, that’s not the case – lead jammers use the power to call it off, for way more things, than the original issue.

Soo, to summarize:

There was a problem, so we introduced a rule/mechanic to fix the problem. But said rule/mechanic has many sideeffects, and the current issues we see in USARS are only possible because of those sideeffects.

So, purely technically speaking, the core gamemechanics of the “modern classic” roller derby game, are NOT “just fine”. The current issues are NOT only an issue of skill. There is an actual problem with the rules/gamemechanics, but so far, we don’t know how to fix that in a way that doesn’t cause even worse problems. Thus until now, we left it at that, and tolerated the sideeffects (and, joking a bit, some people seem to have gone beyond denial, anger, bargaining, depression to “acceptance”, and now consider it “part of what the game is about”. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature).

Posted by WindyMan on 16 November 2013 at 11:07 pm

This is a problem, but one that’s unrelated to the call-off mechanic. Simply put, it is absolutely critical that players from both teams line up to start a jam in fair and equal position. Roller derby is a race, and like any race it only makes sense if both teams start from the same starting point. That way, whatever position the teams wind up in during a scoring pass, they both had the the exact same opportunity to get there or prevent it.

If you don’t start every single jam in equal position, more often than not you’ll run into the problem of teams not being evenly distributed within the pack throughout the jam. Because they didn’t start that way in the first place! This is a massive flaw in WFTDA rules, one that USARS is quickly recognizing and one that RDCL has (mostly) fixed.

So this is a problem, but it has more to do with the start of a jam, not the end of it.

If both teams are kind of equal in the pack (with the help of them starting the jam that way) then it comes down to which jammer is faster and better, as per my simple example. But if a team earns a favorable pack position, that puts their (lead or chase) jammer at an advantage—meaning a favorable pack position can actually make up for having a bad jammer and poor pack position can make even the best jammer worthless.

It’s a team game, so what the blockers and pivot does in the pack will affect this equal “distribution” by the time the jammers come around to the back of the pack on a scoring pass. The “score distortion” you refer to in this case is merely the influence the rest of the team has on the outcome of a jam, which is perfectly normal and not a problem. (Unless you meant something else, because I’m not quite sure what you’re saying?)

Posted by Lyxar on 17 November 2013 at 3:49 am

I’m sorry, i should have used more examples to make it easier to understand what i tried to explain.

First, let’s consider a game that is more similiar to speedskating:

There are only two players on the track, who race each other. We would let them skate for 2 minutes, and at the end measure how many metres they skated. Let’s say our measurement teach is super fancy, and we can get it down to centimetres. The amount of cm each skater did skate, would become the “score”. Then after a bunch of such races, we would just add up the scores and declare a winner.

Since we measure distance covered, and can measure centimetre-exact, the score will accurately represent how fast each skater was, compared to the other. It is perfectly fair. Also, if you imagine the score like a scale, it is like a continuum… there are no sudden jumps or spikes in there, that happen only as a sideffect of the scoring method.

What do i mean with this? Well, let’s play this hypothetical game again. But this time, we do not measure cm-exact. Instead, we have beams set up at every metre of the track, and this way measure the score in metres passed. Even though this is probably still accurate enough, we now can already see that the score isn’t that exact a representation anymore, of each skater’s speed, relative to each other. Depending on where each skater is when the 2 minute clock runs out, we might get a score-error that is up to 99cm large. The score of each player now “jumps” in clearly noticable “steps”. This is what i previously meant with “scoring-thresholds”…. there are now spots on the track, at which the score changes from N to N+1, even though – skill-wise – the skill of each skater is a smooth continuum.

Next, lets say we no longer measure the score in distance passed. Instead, we have 8 people on the track, who just skate along the track as obstacles. They do however carefully keep exact equal distance from each other, so that they are evenly distributed around the track. It’s a bit stupid to invent such a game, since those human obstacles might as well be some dumb machines, given that they don’t do anything, but bear with me, this ridiculous thought-experiment, has a point. Anyways, the two scoring skaters, now get points for passing those funny human obstacles. Given that there are only 8 of those on the track, our method of scoring is now even more inaccurate: Not only are those “obstacles” further than a metre away from each other, them being obstacles makes some areas of the track more feasible for an overtake, than others (it would be harder in turns). So, if at the end of the 2 minute clock, one scorer is in the middle of a turn, but the other is not, our score might get “distorted” even more. Plus, if the two scorers also get points for lapping each other, then there is another strange “threshold”, that affects the score: Only by lapping the opponent, could one break through being no more than 8 points ahead of the opposing scorer.

Now, we make those 8 obstacles more active, involved and smart. 4 of them belong to the “team” of a given scorer, and they are allowed to more actively block the opposing scorer. They also no longer are restricted to keeping equal distance from each other, so now scorers skate long distances without getting any points, and then suddenly hit on a “pack” of blockers, and rapidly get multiple points.

There is not even remotely a way anymore now, to call off the race at a random moment (i.e. after 2 mins), and have a fair representation of each skater’s performance in the scores (the example you mentioned).

So, we elect the scorer that is currently in the lead, to decide when the race ends. Naively, we think that after all, it is in the lead scorer’s best interest, to end the race, at a moment where he is not disadvantaged by all those scoring distortions. However, this basically is like a nuclear solution, to the problem. It gives that lead jammer way more power and options, than are relevant to the problem of inaccurate scores. And since the jammer with that power, first is concerend only with his own and his team’s advantage, he might use the calloff-power, to actively *disadvantage* the opponent – like, calling it off to PREVENT a *better* opposing scorer from scoring! Notice that this technically actually goes against the original purpose, which was to accurately represent each jammer’s and team’s skill in the final score, *NOT* preventing their skill from showing up in the score-differential!

And of course, the power to call it off, can be used also for less “egoistic” means – like, ending the jam out of fear and being paranoid about the opponent scoring ANY points, even if that means, that one oneself doesn’t score as well, and even though one is in a better scoring position.

Now, you correctly point out, that when such things happen, the players often do it because of lack of experience, or skill, or encouragement, or whatever. That might be true, but it doesn’t change the fact, that players are capable of doing this in the first place: Why is this even possible to happen so easily, given those uses of the calloff mechanic, have nothing to do with the original score accuracy problem? Answer: Because so far, no one has come up with a better solution.

Posted by Eric Anderson on 11 November 2013 at 5:01 pm

The better rule would be that the jammer can not call it off until he or she has passed or been engaged by one opposing blocker, including the opposing jammer”